Maybe there’s something to be said for doing just enough.

It’s taken me a solid 40 years to reach this realization, and I’m not sure I fully believe it yet, but I’m getting there. Slowly. Day by day and pointless elementary school homework assignment by pointless elementary school homework assignment.

I don’t know when I started caring deeply about perfection, but I know it was very early. I can’t remember a time when I didn’t obsess over getting 100s on tests at school or playing a game of baseball without making a mistake.

I vividly remember in sixth grade, sitting at my little elementary school desk with the cubby hole under the writing surface where you crammed books, papers, and pencils, tears beginning to well up in my eyes as I slowly realized I had made the gravest of errors. It was a truly unforgivable mistake.

The class had completed some sort of quiz or test. The teacher instructed us to exchange papers with another student, and then she went through the answers while we graded the other person’s paper. In retrospect, this seems like an unnecessarily cruel and public way to grade an assignment, but there were no considerations for children’s feelings back in the late 1900s.

After the teacher read off the first couple of answers, the girl grading my paper looked perplexed.

Anastasia Shuraeva | Pexels

Anastasia Shuraeva | Pexels

She raised her hand and explained what I had done. I don’t remember what it was that I had done, exactly, but I know I messed it all up… terribly. I think I must’ve misread the instructions or something so the bottom line was that all my answers were wrong. A clear F. Failure. Or rather, H for humiliation.

The girl, who just so happened to be very cute and nice and popular (that didn’t help matters), looked at me with concern in her eyes. Of course, her face was starting to look a little watery from my perspective. Almost as blurry as if I’d taken off my Coke bottle eyeglasses.

I immediately attempted damage control because the first thing every perfectionist learns is that you have to hide your perfectionism at all costs. No one must know that every single mistake literally ruins your life. They can’t know because they can never understand.

At least, that’s what I always assumed. I forced a smile. I gave a little chuckle like, “Oh, how silly of me… I’m so glad I DON’T CARE AT ALL!”

“Oh, I guess I messed that up,” I said out loud, mustering every bit of willpower and energy I had to try to prevent my voice from cracking because of the tears that were definitely coming. “Haha!”

I wanted to dash out of the room and fling myself into the nearest retention pond. Let the alligators consume my carcass.

Instead, I sat there and took my humiliation like a boy. It was fine. It clearly didn’t take me long to get over it.

So, against that backdrop and personal history, I now attempt to parent three children who very often seem to display very little concern about any traditional measures of “success” or “achievement.” When I was in school — all levels, from first grade through graduate school — I looked forward to test days with a borderline pathological zeal.

Sure, Christmas morning was great, but what really got the blood pumping was standardized testing day in the fourth grade! I could hardly sleep the night before, visions of test result sheets with little Xs filling up the whole page dancing in my head. (Back in the old days, the test results for each subject were shown visually as a kind of dot plot, so if you achieved the 99th percentile on everything, your sheet would be full of Xs.)

Intoxicating stuff. Now, my children hardly even know when they have a test and would never know their results if I didn’t tell them. As long as they are doing enough to pass, they don’t seem to care when the complete disaster of a test grade pops up periodically in the online grade portal. (You might be surprised to learn that I check the portal at least once a day.)

Is my children’s way a better way to live? Objectively, yes. Is it an easy adjustment for me? NOPE!

Last year, my oldest son, who is in middle school, scored just below the cutoff on the annual state test (literally one point below), so he was not placed into the most advanced class for his seventh-grade year.

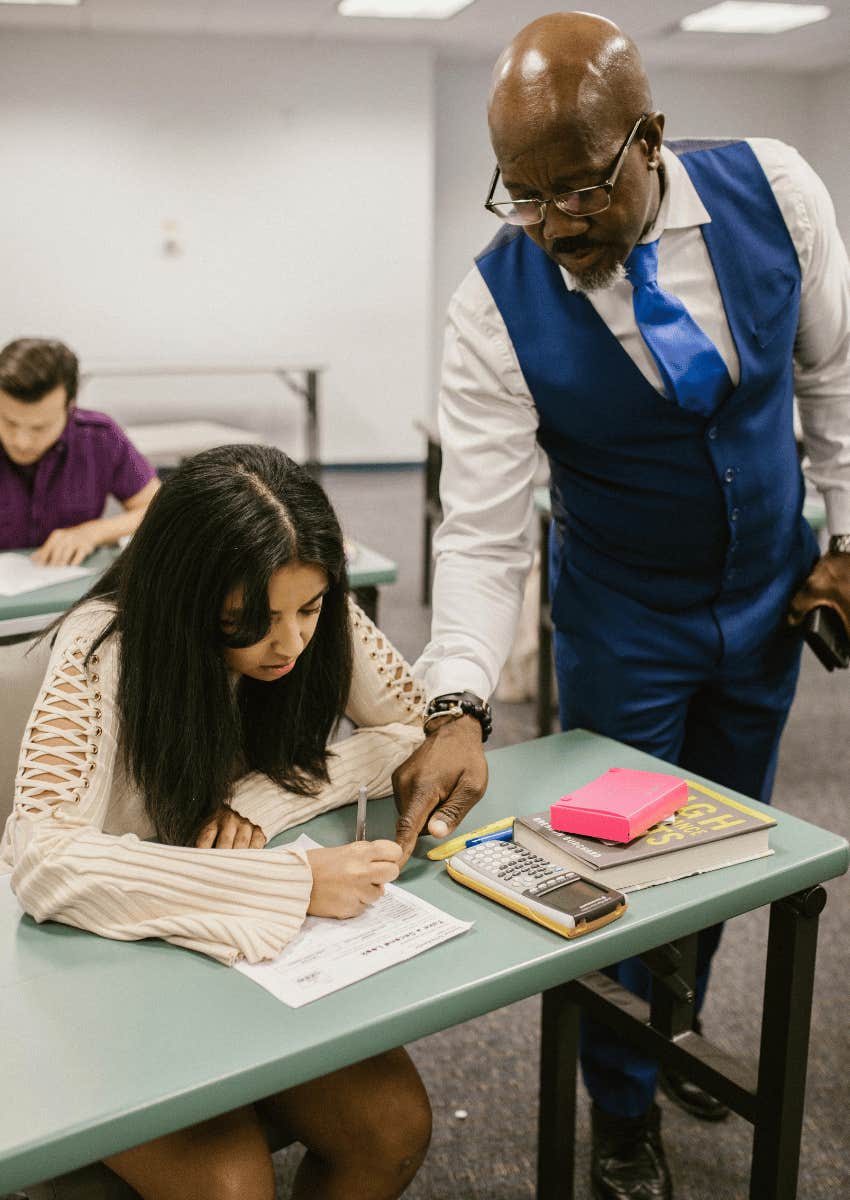

RDNE Stock project | Pexels

RDNE Stock project | Pexels

I was enraged. I enquired with the assistant principal via email. I asked, since my son had made straight As in the subject all through sixth grade and scored fine but not outstanding on the standardized test, if he could be placed in this higher-level class. The guy replied, “No. We can only go by the test.”

I was unreasonably mad about this. I wanted my kid in this class which is, undoubtedly, the same as all the other classes because they are in seventh grade. But that’s beside the point! It’s all about, I don’t know, winning and my kid achieving a status symbol that only I care about!

Patterns forged in the fires of childhood are very difficult to overturn. I imagined myself following up with the assistant principal. Going all in.

“You mean to tell me that getting all As in a sixth-grade class doesn’t mean anything??”

“Yes,” he would certainly reply in that patronizing way school administrators have mastered after years of dealing with lunatics like me.

“Sir, everyone knows that middle school and elementary school grades are completely meaningless. We just give them out so the parents who care about grades will be happy.”

“Wait. You also mean to tell me the fact that I got all As literally my entire academic career from first grade through college is meaningless?”

“Yes, of course. Just look at how your career has turned out.”

Fictionalized assistant principal does have a point. In the end, my personal obsession with perfection got me nowhere of value.

Lubomir Satko | Pexels

Lubomir Satko | Pexels

I could’ve made Cs, and heck, even a D or two (still tough to even type any of this out), and I would’ve very likely ended up in the same place I am now. And that place is a pretty good one, to be clear.

I have a great family. I’ve managed to carve out a work life that is unorthodox but fun, flexible, and fulfilling in some ways. And most importantly, I’ve had a front-row seat for my children’s entire childhood. (Well, the seat is a bit misleading, probably, but you get the gist.)

From my perch in the front row, I’ve had the chance to observe how they are different from me in the best possible ways. They are generally more relaxed, less stressed about unimportant things, and less likely to care about meaningless awards and talismans of “success.” I’m happy for them.

I hope they continue to find that balance. Maybe they can teach me a thing or two about what real success looks like because I’m still very much a work in progress.

When I’m managing homework time or discussing school and testing and all things achievement, I have to keep a large metaphorical stick handy to beat away my heavily entrenched feelings about winning and the importance of being perfect at everything. Sometimes I forget the stick.

It lingers, dusty and neglected, in a cluttered corner. I slip up and say things I shouldn’t. Push too hard. Make my kids feel bad about things I know as a rational adult don’t matter. Then I feel bad. It is much less than perfect. I take deep breaths. Apologize and reset.

I try to do better next time. Because that’s what’s it all about. Learning, growing, understanding myself a little more each day. Hopefully helping my children discover their best and most authentic selves while they help me rewire those neural pathways that compel me to care deeply about getting ahead and looking good in the eyes of hypothetical others.

And when I get a little down about it all. When I feel like I’m a failure because I can’t just chill out and let the little things go. I sneak off and rummage through the metal filing cabinet in the closet to dig up one of my old standardized test reports from the last century. Because sometimes, a recovering perfectionist like me still needs my achievement fixed. No matter how meaningless.

Andrew Knott is a writer, editor, and father of three. He is the author of the novel Love’s a Disaster (2024), and his writing has been featured on Yahoo, Parents Magazine, Medium, and The Washington Post.