Many of us are familiar with Dr. Elizabeth Kubler-Ross and her five stages of grief model, put forth in the 1969 book, On Death and Dying. According to Kubler-Ross, grief involves a pathway through denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and finally, acceptance.1 While this framework could be validating for some, if viewed through a non-linear lens, researchers have since discovered that the stages of grief don’t tell the whole story of navigating loss.

Today, researchers are finding that there is no one, right, or healthiest way to grieve. No stages, steps, or prescriptions embody the grieving experience; rather, storytelling is at the heart of the grieving process. Survivors naturally tell stories of loved ones who have passed that describe the depth of their relationship and their societal and cultural context. “Within these shifting parameters, our stories of our dead are interpretive, creative, and active, and our griefs are as idiosyncratic and diverse as the relationships to which they pertain,” write O’Connor and Kasket, authors of “What Grief Isn’t: Dead Grief Concepts and Their Digital-Age Revival.”2

In today’s digital world, social media often misleads mourners with a definitive and uncritical portrayal of the 5-stage model of grief—a linear, rigid prescription that can be difficult, if not harmful, to follow.3 This can shame and alienate those who do not relate to the stages of grief experience. On the other hand, storytelling stands by as a universal outlet for processing loss.

.jpg?itok=8EoUUZxN)

Author Emma Grey shares her perspective on grief, loss, and storytelling.

Source: Hannah Robertson/Used with permission

Author Emma Grey knows the grief experience all too well—after losing her husband in her 40s, she used storytelling to work through some of her feelings after loss by writing the bestselling novel, The Last Love Note, a heartbreakingly authentic story of a young widow finding love after loss. Her latest book, Pictures of You, touches on loss through a different lens, even delving into the complicated grief experience of someone whose relationship was difficult, to say the least.

Grey generously shared her perspective on navigating grief and loss through storytelling with Psychology Today.

Research shows that there is no one right or healthy way to grieve—no stages, steps, or prescriptions. What has been your experience with grief, and how do you hope to portray it authentically in your books?

EG: I’ve had many losses, but two were of primary people in my life—my husband, Jeff, suddenly to a heart attack when I was 42, and my mother, at 91, after a long battle with dementia. When Mum died, I thought I was prepared. I thought I knew grief. I thought I was an expert in loss because I’d come through the loss of Jeff.

What surprised me was to find I was really only an expert in losing Jeff. Not Mum. And that grief is as unique as the different relationships in our lives.

I’ve written about the loss of a husband in The Last Love Note and the loss of a mother (and the loss of self, and friends and family) in Pictures of You. In each case, there was a moment where I thought, “Should I pull this back? Should I say less, and make this feel safer for me, as the author?” It’s deeply personal to fictionalize your experiences, but also deeply helpful, if we can rouse the courage to tell it like it is.

So I went even deeper into the rawness of loss, and the response from readers has been quite extraordinary and very healing at times. I spent hours every day for several months after The Last Love Note came out, just responding to readers’ messages on Instagram. This is such a universal experience.

University of Memphis psychologist Robert A. Neimeyer concluded in his scholarly book Meaning Reconstruction and the Experience of Loss (American Psychological Association, 2001): “At the most obvious level, scientific studies have failed to support any discernible sequence of emotional phases of adaptation to loss or to identify any clear endpoint to grieving that would designate a state of ‘recovery.’” Do you agree that there is no end to grieving someone we love? How does grief evolve over time?

EG: I think grief expert Megan Devine put it well when she said, “Some things cannot be fixed; they can only be carried.”

Grief lasts as long as love lasts. My experience has been that, over time, it becomes easier to carry. Life can grow around the loss, but the loss never leaves.

Eight years on from losing my husband, waves of grief can still dump me so deep into the emotion that it might as well have happened yesterday. But those waves are much further apart now. I recover from them much more quickly. At first, the loss was all-encompassing. Now, it feels more like the constant backdrop to my life. It is always there, but other aspects of life can take center stage.

When your child loses a parent, they face a new reckoning with grief at every developmental stage. My 14-year-old son is processing a different sort of loss now from that of his 5-year-old self who lost Daddy so suddenly. He’s discovering, as he gets older, the depths of what he’s lost, the rising tide of unanswered questions, and the experiences and achievements his father will never see. Even now, writing these words, I’m tearing up—so yes, it’s true that grief evolves, but never ends.

How has experiencing such a significant loss changed your perspective on death and grief?

EG: It has brought life and love into sharper focus. I remember kneeling beside my husband shortly after he had died, and being acutely aware of my own heartbeat beside his stillness. I had never been so conscious of the air going in and out of my lungs. The death of a loved one has a way of making it resoundingly clear that the very breaths that we take are a privilege. They are numbered.

I’ve learned a lot about taking chances, seizing opportunities, and loving people deeply. I’ve learned to let go of what truly doesn’t matter and to pay closer attention to what does.

But this comes with a word of warning, too. It isn’t feasible to live every day as if it’s your last. Life can be tricky. Some days are difficult or disappointing or mundane. I don’t think we should pressure ourselves to make the most of every single moment. But certainly, know that the light in life can seem brighter when you’re viewing it in the darkness. Always look for that light.

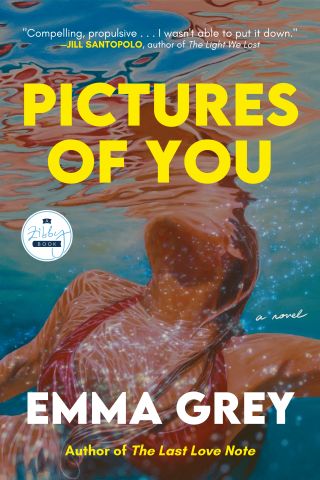

“Pictures of You” offers readers a reminder that it’s never too late to start again, to reinvent ourselves and to draw a line in the sand and step over it into a new future.

Source: Zibby Books/Used with permission

What do you hope readers take away from spending time with your latest, Pictures of You?

EG: Readers may recognize themselves or their friends in the twists and turns of Pictures of You. It’s about two very different kinds of slow-burn relationships — one that burns hot and takes years to simmer into something more sinister, and one that rises from those ashes.

It’s a novel about first love and second chances, about the insidious ways a relationship can go terribly wrong and about the steadfastness of the friends who carry us through. And it’s a reminder that it’s never too late to start again, to reinvent ourselves and to draw a line in the sand and step over it into a new future.