In the years since the 1964 Surgeon General’s report revealed that smoking caused cancer, tobacco use has declined significantly. Only 12% of American adults smoke cigarettes today, compared to nearly half of American adults in 1965. This is a sea change. Could proven anti-tobacco efforts also decrease opioid addiction, reducing deaths from overdoses? It’s an intriguing question.

The United States leads the world in overdose deaths, particularly from opioids. Over the past five years, 500,000 Americans have died from overdoses, at least 200,000 from fentanyl alone. The death toll from fentanyl alone surpassed the combined deaths from the Vietnam and Korean wars.

The opioid crisis is the most severe sustained public health crisis in the U.S. in terms of human cost. This is unacceptable. We need all the help we can get from evidence-based life-saving treatments and preventive approaches. Yet recent analysis suggests we are under-investing in prevention and in applying lessons learned from programs that slashed smoking.

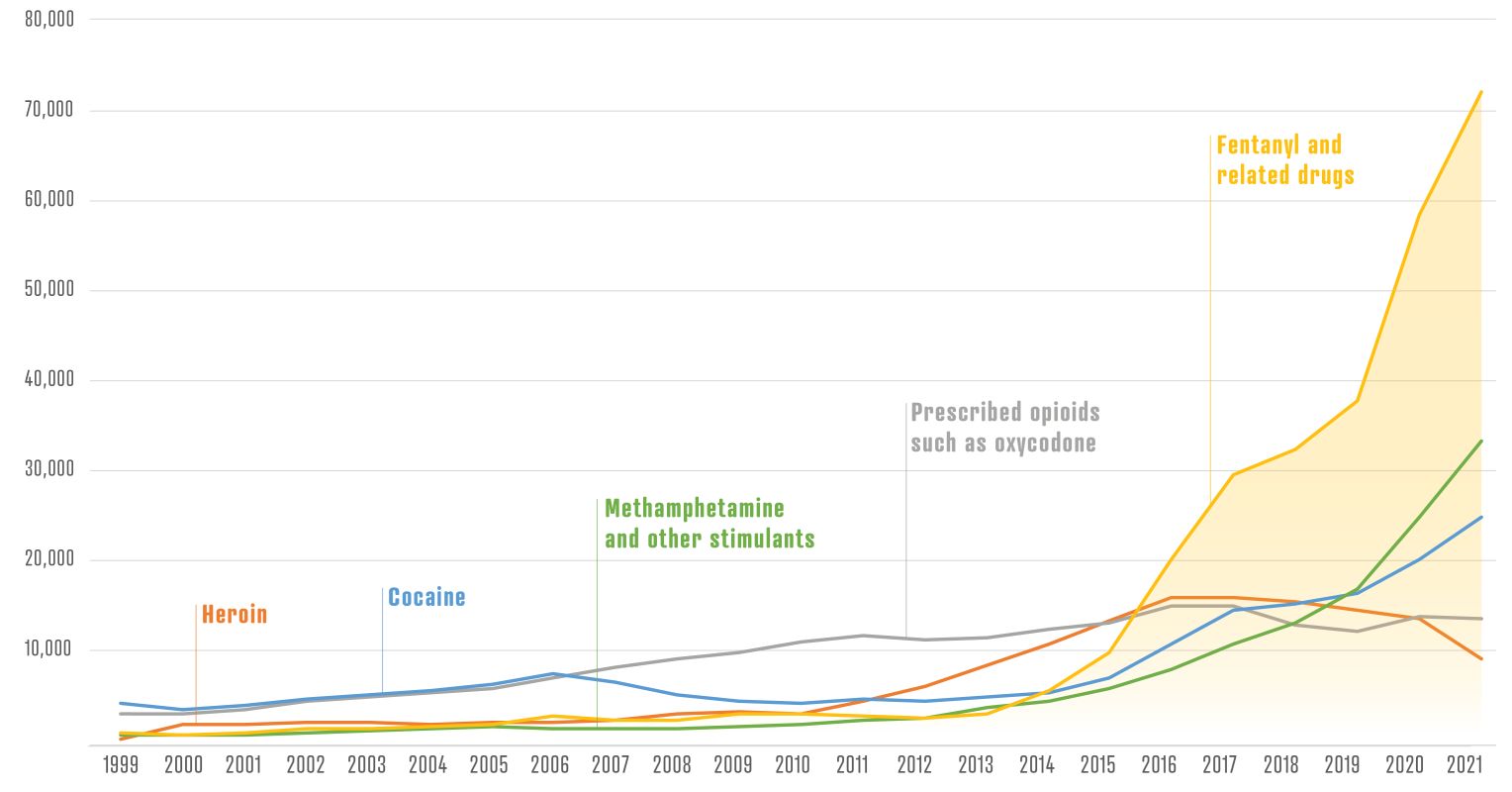

Overdose deaths were rare in the Woodstock ’60s. Throughout the 1970s, there was increasing heroin use, but overdose deaths remained below 10,000 per year. By 2009, overdose deaths had tripled to 30,000. The opioid crisis began escalating, and overdose deaths zoomed to 70,000+ a year by 2010. It didn’t seem possible it could get worse, but by 2023, 107,500 people died from drug overdoses.

Looking Back at Smoking

In the Mad Men 1960s, half of American adults smoked. Doctors smoked! Smoking cigarettes was considered relaxing healthy behavior until the Surgeon General reported that smoking causes cancer. A concerted nationwide effort began that was highly effective in decreasing smoking.

Could some elements of our nation’s anti-smoking campaigns also decrease opioid abuse, opioid use disorders, and opioid deaths?

In the wake of the Surgeon General’s report, doctors began asking patients about smoking, and those who smoked were counseled to quit. In addition, pharmacological interventions were developed to help people detox from nicotine. Everyone, it seemed, tried to help smokers attempt to quit; nicotine replacement patches, newer pharmacotherapies, and advertisements relaying the dangers of smoking helped smokers exert control over cravings and relapses.

Warning Labels

The Surgeon General’s report led to the Federal Cigarette Labeling and Advertising Act of 1965, requiring health warnings on cigarette packaging. The Public Health Cigarette Smoking Act of 1969 banned cigarette advertising on television and radio. These were among the first federal actions to control tobacco use, setting a precedent for future regulations.

Of course, we can’t put warning labels on illegal opioids because, well, they are illegal. But there are other actions we could take.

Smoke-Free Laws

In later decades, laws mandating “smoke-free” workplaces, restaurants, and public spaces limited where smoking could occur, diminishing smoking’s social acceptability. Such restrictions normalized smoke-free environments, encouraging people to quit. The campaign to protect nonsmokers from second-hand smoke was pivotal in health and legal efforts to restrict smoking.

Similarly, banning public drug use has been proposed in many cities. Recent laws such as the HALT Fentanyl Act may reinforce local efforts to stop public injection of fentanyl in parks and schoolyards. Other initiatives could raise prices or disrupt fentanyl supply channels, ease of selling, and use, as well as reduce harm to users.

Anti-Smoking Programs

Anti-smoking advocacy groups, including the American Cancer Society, American Lung Association, and Action on Smoking and Health, best known as ASH, launched media campaigns emphasizing the dangers of smoking and second-hand smoke. The campaigns shifted the narrative to smoking as a health issue affecting everyone. By 2009, federal law banned smoking in all government buildings, reinforcing the shift.

The CDC’s “Tips from Former Smokers” highlighted the severe health consequences of smoking, often through personal stories of former smokers that created an emotional response deterring smoking initiation among youth and motivating quit attempts.

Anti-smoking campaigns villainized tobacco and tobacco companies while reinforcing the harm done to people by tobacco. Many school-based prevention programs target youth directly to prevent smoking initiation since smoking often begins in adolescence.

To combat today’s overdose and fentanyl deaths, programs that publicly declare any non-prescription opioid/fentanyl use harmful without stigmatizing the addicted person could be very effective.

One of the most memorable anti-smoking campaigns, created in the 1970s, featured stark messages highlighting smoking-related diseases like lung cancer and heart disease. The ads included unsettling visuals of smokers experiencing severe health conditions—deploying disgust to stigmatize smoking. The goal was to make smoking appear unappealing and unhealthy, to counter the aura of glamour earlier attached to smoking in movies and other cultural imagery. Recent media coverage of the drug xylazine featured what appeared to be skin-lesioned zombies.

Oddly, it has not been made clear that opioid or fentanyl use is risky and often ends badly. Illegal opioid use is a fast track to a family tragedy, as 321,566 American children were orphaned by overdose between 2011 and 2021 alone.

So many opioid overdoses continue to occur because no one has stepped up to stop unending new users from trying recreational opioids. As NIDA Director Nora Volkow observes, at some point, use becomes an addiction with accompanying loss of free will and control. This is why prevention of opioid abuse is so important. Research suggests that many people still underestimate the dangers of fentanyl. Broader public awareness of the dangers could be a critical deterrent.

Would Stigmatizing Opioid Abuse Work?

Applying tobacco-era stigmatization methods to illegal opioid use is complicated. Progress has been made in encouraging treatment and reducing shame and stigma. There is a concern that intense stigmatization of fentanyl or opioids (and not opioid addicts) could reverse such progress. Stanford’s Dr. Keith Humphreys suggests more explicit messages around the dangers of recreational fentanyl would work well without alienating people needing treatment or opioids for medical treatment.

Stricter Regulation of Opioid Production

Given fentanyl’s potency, ease of production, and ongoing contamination of other street drugs, anti-fentanyl solutions must combine law enforcement, international regulation, public health initiatives, and technological tools. Stricter regulation and monitoring of precursor chemicals could help, too.

For example, fentanyl production relies on ingredient chemicals produced in China and India. Increasing scrutiny of chemical exports and pressure on and collaboration with these countries to regulate the chemicals is essential. We need to prevent precursors from reaching illicit manufacturers, often in Mexico. Expanded DEA-law enforcement partnerships in Mexico are required.

Follow the Money

According to Robert DuPont, M.D., head of the Institute for Behavior and Health, “The killer fact in overdose prevention is this: Most individuals who die of an overdose have serious substance use problems. They know about the reality of the overdose epidemic: many have experienced non-fatal overdoses and have friends who have died. And yet, they pay for their fatal dose of drugs. No policy will slow the drug supply unless it stops the remarkable flow of money from drug users to drug dealers. That is true for legal drugs and for illegal drugs.”

Targeting the flow of fentanyl finances needs additional emphasis. Criminal organizations trafficking fentanyl often rely on cryptocurrencies and secretive and sophisticated financial networks. Increased transaction monitoring and seizing of cartel assets can curb their financial resources. Increasing penalties for trafficking synthetic opioids are needed, explicitly targeting fentanyl traffickers.

Summary

A massive reduction in smoking rates resulted from a multifaceted public health approach, making tobacco companies villains and smoking less socially acceptable, and limiting harm through education/media prevention campaigns, taxation, smoke-free policies, and raising awareness of tobacco effects. The combined efforts created a tipping point in public health at which smoking was no longer perceived as normal. Many smokers quit.

The transformation in social norms, treatment availability, and use of systematic public health measures illustrate the effectiveness of environmental and behavioral approaches. Some of the same tactics could help decrease the number of people trying illegal opioids and relapsing once treated, averting at least some (and maybe many) instances of overdose and addiction.