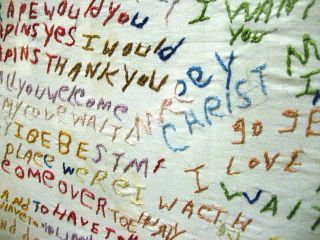

Cloth embroidered by a patient with schizophrenia. An example of word salad. Glore Psychiatric Museum, Saint Joseph, Missouri.

Source: Wikimedia Commons/Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License. Author: cometstarmoon. Uploaded by CopperKettle.

“If Trump and Harris were forced to eat their words, at least they’d have plenty of fiber in their diets,” writes Frank Bruni, longtime New York Times contributing writer and professor at Duke University (online Opinion, 10/31/24). Those in the media have accused both candidates of tossing up their version of word salad, and thousands of references have appeared in recent Google searches about the current political scene.

For Bruni, there is no comparison between Harris’ “semantic slaloms” and occasional evasive and digressive answers and Trump’s “verbal incontinence” and “twisted journeys across random subjects with scant connection.”

Continues Bruni, “Adjust your diction diet. Why can’t Harris be cooking up a word bouillabaisse? … Why can’t Trump be gorging on shepherd’s pie of jumbled verbal ingredients?”

“A Salad in a Skull.” Image of Victor Hugo meditating, 1862. The title is a parody of a chapter in Hugo’s book “Miserables.”

Source: Copyright Photo credit: Patrice Cartier. All rights reserved 2024/Bridgeman Images. Used with permission.

Bruni is correct. The term is not only overused, but it also does not apply. And while each candidate may seem “green in judgment” to their critics, as Shakespeare’s Cleopatra described her “salad days” (1608), neither Harris nor Trump exhibits speech that exemplifies word salad, which is a specific type of thought disorder.

It has a history long enough to have wilted by now. Present-day journalists and pundits may be using the term metaphorically. They should appreciate, however, that they are misappropriating a technical term from the annals of psychiatry that is still in use by mental health clinicians today.

Reportedly, the expression was first used in 1894 at the May meeting of the Association of German Alienists and Neurologists.

Specialists who treated those with “mental alienation” were alienists, who believed that all mental disorders resulted from brain lesions.

German Professor Emil Kraepelin described a group of patients with meaningless jabber, i.e., “word salad.”

Source: Copyright: Wellcome Trust Collection. Used with permission.

Though the word psychiatre was introduced in France in the early 19th century, its use did not become widespread until the beginning of the 20th century when it replaced the term alieniste (Bogousslavsky and Moulin, 2009).

It was at this 1894 meeting that Dr. Emil Kraepelin, a German professor of psychiatry famous for his classification of mental patients, described “a peculiar group of insane patients, who among other distressing symptoms, exhibited the most striking phenomenon,” a tendency to coin new words and “drop into a meaningless extravagant jabber” (The Medical Standard, 1895). Hearing Kraepelin’s description, the Swiss professor of psychiatry and researcher Auguste Forel (Parent, 2003) called this jabber worstsalad; translated from the German, it became word salad.

Word salad, or more specifically, incoherence, is one of the many manifestations of disorganized or disordered thinking in which words are strung together in a bizarre, inexplicable, illogical fashion. It is typically seen in psychotic individuals, who may also demonstrate an inability to deal with reality, display grossly abnormal behavior, and experience hallucinations and/or delusions (DSM-5.)

It was Eugen Bleuler, one of the fathers of modern psychiatry, who coined the term thought disorder and emphasized its importance in diagnosis: He regarded the “loosening of associations” as pathognomonic of what he called schizophrenia (i.e., “a splitting in the fabric of thought” [Andreasen, 1982]).

Thought is a “complex” system involving pattern recognition, concept formation, and analytic processing, and thought processes themselves cannot be observed directly but only inferred (Andreasen).

Thought is critical to how we understand other people and how we make ourselves known to others. Any breakdown can affect our psychological and social well-being and our general ability to adapt to the world. A thought disorder is “multidimensional” and reflects disturbances in thinking, language, and communication (Hart and Lewine, 2017).

Some researchers distinguish a disorder of the form of thought (i.e., formal thought disorder) from disorders of the content of thought, such as hallucinations and delusions; others emphasize that a formal thought disorder “has not been adequately defined, and its usage tends to be fuzzy and imprecise” (Andreasen).

The evaluation of thought is part of the mental status exam conducted by mental health professionals. Other components of this diagnostic exam include assessing appearance and general behavior (e.g., grooming, eye contact), motor activity (e.g., posture, rigidity), speech (e.g., volume, rate), mood and affect (e.g., subjective and objective), insight (e.g., awareness of illness), sensorium (e.g., level of consciousness), and judgment (e.g., recognition of consequences; Snyderman and Rovner, 2009).

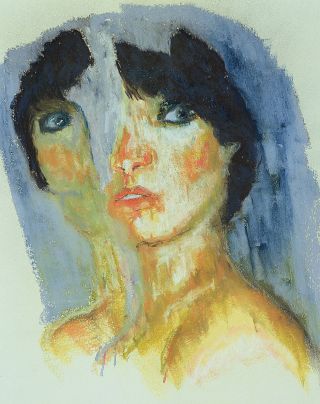

“Splitting,” by English artist Stevie Taylor. Private Collection.

Source: Copyright Stevie Taylor. All rights reserved 2024/Bridgeman Images. Used with permission.

Disordered thinking, which likely has both genetic (Kircher et al., 2018) and environmental influences, can vary in severity over time, particularly in the context of anxiety or fatigue, and it can be reversible (Hart and Lewine; Tan and Rossell, 2020). Some researchers maintain that a severe, persistent formal thought disorder, though, is predictive of poor social functioning, unemployment, and relapses (Oeztuerk et al., 2022).

We now know that disordered, derailed thinking, which can include not only word salad but also the creation of new words (neologism), as well as tangential, circumstantial, pressured thinking, or even poverty of thought, can occur in other conditions, such as mood disorders, including mania and depression (Hart and Lewine; Tan and Rossell; Oeztuerk et al.).

Further, Glasner has described what he has called a “soft thinking disorder” (i.e., benign paralogical thinking), which is not psychotic and “common” in both clinical and nonclinical populations (1966).

These individuals, while they have “idiosyncratic thinking,” do not demonstrate word salad or any gross disorganization of thought, nor do they have bizarre ideation, delusions, hallucinations, a tendency to deteriorate, or an inability to assess reality accurately. They may demonstrate tangential, circumstantial, or even irrelevant responses. In other words, their thinking defect is an “isolated one”; it is the form of thinking rather than the content of thinking, which is abnormal (Glasner).

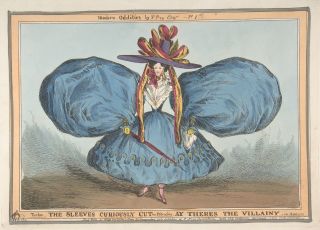

“Modern Oddities,” by British artist William Heath, 1829. During the 19th century, women’s fashions included “salad plate hats,” which were wide-brimmed and decorated with feathers and ribbons. The title is taken from Shakespeare’s “Taming of the Shrew.”

Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art. Credit: Rogers Fund and the Elisha Whittelsey Collection. The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1969. Public Domain.

Significantly, a formal thought disorder “holds the unique position” of being a psychotic condition that can be assessed by others, unlike hallucinations or delusions that rely exclusively on a patient’s self-report (Tan and Rossell; Roche et al., 2015).

There are clinical rating scales to assess a formal thought disorder, but they are not necessarily ideal and can be subjective (Tan and Rossell). Rating scales for a formal thought disorder assess up to 18 different abnormalities in the rate and organization of speech (Roche et al.).

The future holds promise for the use of “data-driven” computerized speech analysis “as one of the most promising objective tools” for research into psychotic conditions (Tan et al., 2023).