In an earlier post on values and personality, I explained why values could be considered a type of personality trait. Personality traits are typically defined as “consistent patterns of thoughts, feelings, or actions that distinguish people from one another” (Johnson, 1997, p. 74). Values are often defined similarly, for example, “Values are dispositions to experience affect-laden cognitions that draw people toward desired outcomes” (Longest, Hitlin, & Vaisey, 2013, p. 1500). (Cognition and affect are technical terms for thoughts and feelings, respectively).

Thoughts or cognitions can refer to many different mental processes or contents. In the case of values, we are talking about beliefs about what is good, right, important, and worth striving for (and sometimes worth fighting or even dying for). These beliefs are not neutral and disinterested; they are accompanied by strong feelings or affect, which motivate us to pursue what we value.

My previous post further explained why, even though values are part of personality, most research on values has been conducted by social psychologists such as Milton Rokeach, Shalom Schwartz, and Jonathan Haidt rather than personality psychologists. It is because Gordon Allport’s early taxonomy of personality traits, from which the Big Five model of personality emerged, intentionally omitted value-laden trait terms. Interestingly, despite attempts to keep values out of personality, empirical research has demonstrated that Schwartz’s and Haidt’s value measures are meaningfully related to the Big Five. I ended the previous post with a promise to discuss additional issues about personality and values, such as how moral values differ from other values and how values can guide our choice of careers. This current post delivers on that promise.

Types of Value

When people hear the word “values” they often immediately think of morality. But moral values refer specifically to good behavior, behavior that we aspire to and expect other people to aspire to. We can also talk about aesthetic, political, and other kinds of values. Natural beauty or art has aesthetic value because creates a good state of mind (McCrae, 2024). Government policies have political value when they create desirable outcomes such as liberty, security, fairness, and order.

Beneath the potentially bewildering array of different “types” of value, the common denominator is a belief that something is good and desirable. Moral virtues lead to good actions. The best art produces desirable states of mind. Effective government policies lead to good social functioning.

Good and Bad Assume Meaningful Goals

I think it is important to understand that the concepts of “good” and “bad” inevitably require goal-seeking organisms. In the words of neuroscientist Kevin Mitchell (2023, p. 66), “Before there were living organisms, there were no good things and bad things. Things are not good or bad in themselves: they only have meaning and value with respect to some goal or purpose. For living creatures, good things are ones that increase persistence. And bad things are ones that decrease persistence.”

Persistence (staying alive and reproducing) might be the most basic valued goal for living organisms, but there are many ways to persist, and therefore a variety of valued goals that people pursue. In a survey of personality and goals, Roberts and Robins (2000) identified 10 clusters of major life goals: economic (achieving career success and wealth), aesthetic (creating and experiencing art), social (helping others), relationship (marrying and having children), political (leading and influencing), hedonistic (having fun), religious, personal growth (finding purpose in life), physical well-being, and theoretical (becoming knowledgeable). Roberts and Robins discovered small but meaningful connections between investment in these valued goals and the Big Five personality traits.

Values and Vocational Choice

Roberts and Robins (2000) used several sources to create their 10 organizing value clusters. One of those sources was Allport, Vernon, and Lindzey’s (1970) Study of Values. I would like to describe the Study of Values because of its relation to vocational choice. We spend an enormous amount of our life preparing for and engaging in work activities, and our success and satisfaction within our jobs has an outsized impact on our economic, physical, and psychological well-being. If we choose a job indiscriminately, just to make money, we risk feeling unfulfilled and unhappy. If we choose a vocation that aligns with our most important values, we are more likely to feel fulfilled. The word vocation means “calling,” as in being called to a higher purpose.

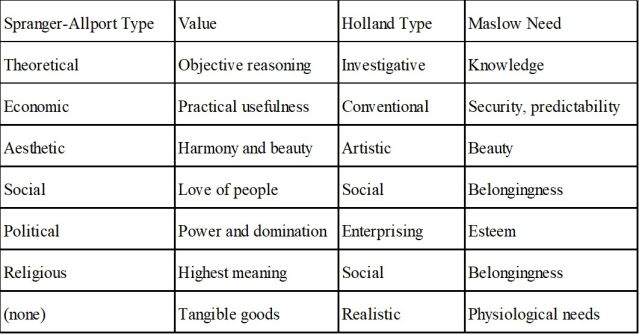

Gordon Allport (ironically, the same Gordon Allport who tried to keep values out of his taxonomy of personality traits) created his Study of Values measure based on the six types of people described by Eduard Spranger (1928). Each of Spranger’s types is oriented to a basic value. These six values correlate empirically with measures of John Holland’s (1994) vocational personality types (Rounds & Armstrong, 2014; Stoll, et al, 2020). Furthermore, each Holland type can be defined by one of Maslow’s basic needs (Johnson, 1994).

Source: John A. Johnson

Value Dilemmas and Priorities

Life is not so simple as the pursuit of one major value. Spranger, Allport, Holland and Maslow all indicated that their short lists of basic values, interests, and needs describe ideal, theoretical types that do not totally define real people. Actual human beings are motivated by multiple values that can come into conflict with each other. For example, self-enhancement can interfere with advancing the interests of other people, and seeking security can reduce personal freedom (Schwartz, 1992). When faced with moral dilemmas and other value conflicts, we need to be aware of our value priorities, that is, which of our values are most important. Completing inventories such as Allport et al.’s (1970) Study of Values and Holland’s (1994) Self-Directed Search can help us become more aware of our value priorities to maximize satisfaction with our life decisions.