I was a giant baby — an ounce away from 10lbs — when I was born. With characteristic stubbornness I refused to be born, arriving after my due date and putting my mother through a lot she claims to still be traumatized from before finally being born via emergency Cesarean.

This was the 1970s, and times were changing in the delivery room. When my older brother was born 5 years earlier, fathers were still stuck in the waiting room with a box of cigars anxiously anticipating a doctor bursting through with the big “it’s a boy!” news. By the time I came around, they had just started allowing dads into the delivery room in our small town hospital, and my dad was amped.

But after the decision was made to cut me out via C-section, my dad got the boot. He had to receive the big news in the waiting room once again. Some men may have been relieved to have been given a free pass on missing all the blood and gore, but I’m sure my dad could’ve handled it.

Even though he did not enjoy all the “girl talk” that he would have to endure with my stepmother, two sisters, and me in his future, particularly anything involving underwear or feminine hygiene, he’s pretty tough and not afraid of a little blood.

When he was a forest ranger in Crater Lake National Park in his early 20s, he sliced his second toe clean in half while chopping log poles for the winter. He stopped chopping wood without much incident that day and had the entire toe removed. His favorite trick for his grandkids these days is to ask them to count his toes.

They always get to 9 and then start over, assuming they must’ve done it wrong. It’s usually around the third try that they realize that Gramps does, in fact, only have 9 toes.

When I was 21 days old, my pediatrician discovered that there was something wrong with my hip rotation.

A trip to the orthopedist revealed a very severe congenital hip dysplasia. I was born with an unformed hip socket a severely under-formed ball joint on my femur.

My parents were told I would need at least one surgery to correct it, probably two. They’d be cutting into bones, or taking bone from one spot and putting it somewhere else.

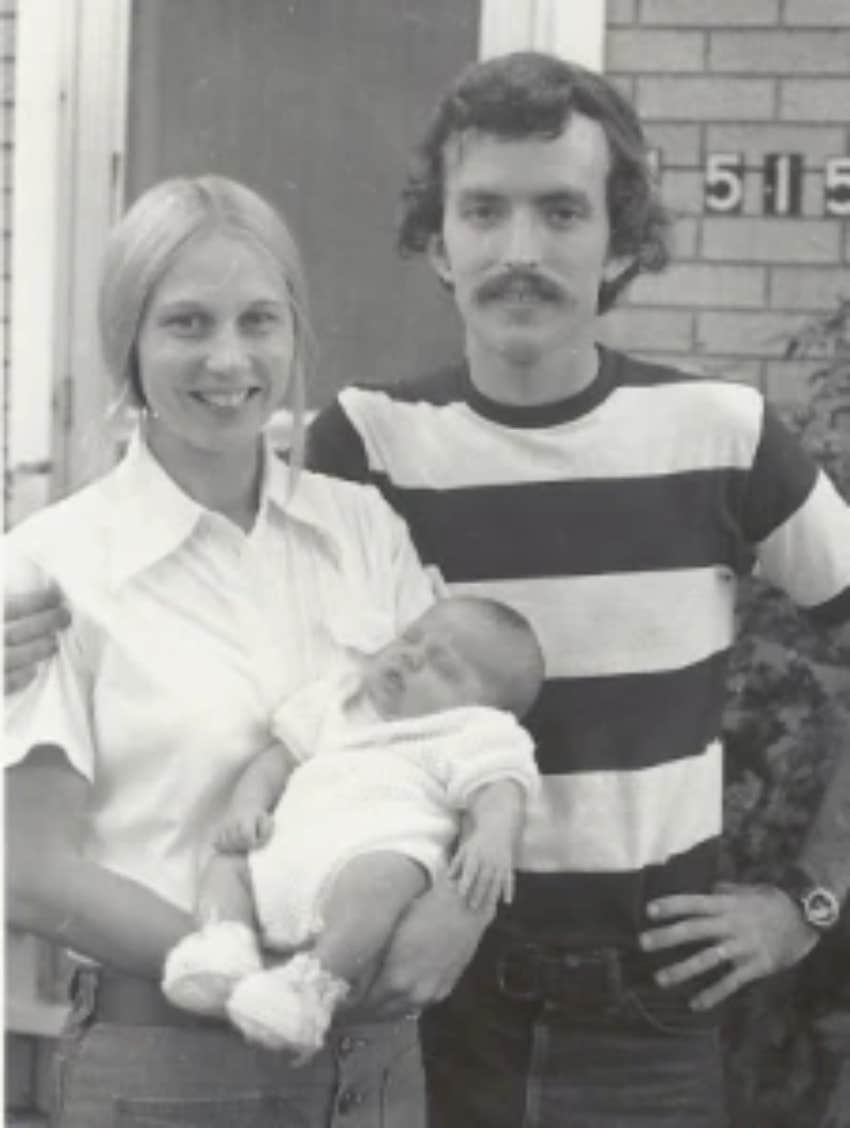

Photo courtesy of author

Photo courtesy of author

My dad didn’t want the surgeries. There are always risks with anesthesia, and cutting into bone increases the risk of dangerous infections.

If you can picture a 21-day-old baby, they are about the most helpless and tiny things you can imagine. At 21 days, babies’ cries sound more like angry cats than the wah-wah-wah we typically think of. 21-day-old babies can’t even hold their own heads up.

But before they had to decide about surgery, I would need to spend 3 weeks flat on my back with my legs in traction to help pull the leg into the right position to allow the bones in the joint to grow into place correctly. This would mean 3 straight weeks in the hospital.

I wasn’t an only child, and my dad had to work. The idea of having me there for so long was overwhelming to my parents. Fortunately, my orthopedist and my dad were equally forward-thinkers. The two of them devised a homemade traction device that would give me a chance to do my traction at home.

My dad, who is an artist who also designs and builds furniture and cabinetry, started with a plywood base on which I would lie. He took a C-shaped piece of metal and attached it on top of the board.

He used tiny pulleys and tiny ropes to create the traction. The ropes attached to a harness on my ankles. For a counterweight, my dad used tiny bags of rice. As time passed, they would add more rice to get the right amount of tension to pull my legs away from my hips. And it worked. At 3 weeks, my tiny not-yet-formed joint was ready for step 2: a spica cast.

According to my parents and my aunts and uncles, I couldn’t have cared less about the cast. I was a happy baby.

Photo courtesy of author

Photo courtesy of author

But I don’t think I truly understood what my parents endured with that cast until I had kids of my own in cloth diapers.

This cast covered both legs and hips to my waist. There was a gap where they would put the diaper. My mom fashioned pieces of rubber pants to put on the edges of the cast so that the plaster and padding wouldn’t wick wetness from my diapers… But of course, it did. And so they sat with one of those tube hair dryers, drying out my cast regularly.

6 weeks later the cast was to come off and a decision was to be made about surgery. If things were growing well, I might not need it. But things were not growing well. They weren’t growing at all. Another cast was put on, and for another 6 weeks, they waited. Soon I was crawling, dragging myself around, commando-style with my elbows.

When the second cast came off, my parents were given the news that the joint was still incomplete and surgery would be necessary. Still, they didn’t want surgery. My dad says it seemed wrong to him, and he wanted to find another solution.

They drove me to Chicago, to Cleveland, to Minneapolis. Every doctor said I would need surgery no matter what.

Finally, at the University of Michigan, they were told they didn’t have to decide right away whether or not to do the surgery. They could wait a little while — not too long — and see what happened.

This felt right to my dad, and so they went home relieved but still cautious. Were they doing the right thing? Had they already waited too long Amazingly, a week later, my socket started to grow. No surgery was ever needed.

My babyhood and young childhood were spent in and out of that orthopedist’s office — Dr. Sid Rhein. I remember him well. I remember having to go in, have an x-ray taken, and walk down the hallway while he watched my gait.

My hips grew in relatively normally. I’ve always had some bursitis and joint pain, but I’ve never not known bursitis, so it didn’t bother me much. My parents expected me to do everything every other kid did, and so I did.

I even ran track like my dad and brother. We all ran the same race: the 440 and the mile relay. Running, believe it or not, is good for you, one study published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology states that running 10 minutes a day can extend your life.

A few years ago, while I was in a routine of running 40-50 miles per week, my left hip, which is my more pesky one, started to bother me. I got a referral to an orthopedist at UCLA Medical Center who was supposed to be the best.

I was nervous to go, afraid I’d finally need the surgery my parents had insisted I shouldn’t have, or afraid this fancy doctor in this ridiculously expensive medical facility would look at my x-rays and somehow know that my traction was weighted not by a fancy device but with two tiny bags of rice.

Instead, the orthopedist looked at my x-ray and pointed out all the things I already knew: That my femur doesn’t curve properly into the socket. The socket itself is slightly shallow and has a lip that irritates the bursa sac around the joint.

I had severe dysplasia at birth, I told him, nervously, about the home-made traction system my father had invented and built for me, about the many hospitals and specialists we visited, and about my parents doing everything they could to avoid surgery.

He was poker-faced. I bit my lip.

“Well, it worked. This is about the best outcome I’ve ever seen in this severe case of hip dysplasia. This is what happens when caring parents advocate for their kids.” Thanks, Dad. (You too, Mom!)

Joanna Schroeder is a parenting writer, editor, and media critic with bylines in The New York Times, The Boston Globe, Esquire, and more. Her forthcoming book Talk To Your Boys: 20 Crucial Conversations To Have With Your Tween & Teenage Sons will be available in 2025 via Workman Publishing.