Unconscious memories flow beneath the surface of our daily lives, emerging when sensory cues in the environment, waves of familiar emotion, or specific contexts trigger remembrances of events from the past that we’ve buried deep within. Research shows that repressed memories, especially those related to fear, can be brought to the surface when we return to a similar mental or physical state as when the memory was first formed (Squire LR, Dede AJ, 2015; Northwestern University, 2015).

Memories can reveal themselves through dreams, slips of the tongue, or even in our automatic responses to certain triggers in everyday life (Scalabrini A, Esposito R, Mucci C, 2021; Ruch, R. S., 1972). It’s no wonder that the interplay between the present moment, our conscious memories (along with the narrative we’ve constructed about our life experiences), and the unconscious memories within create a complex template for our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors as we move through our lives.

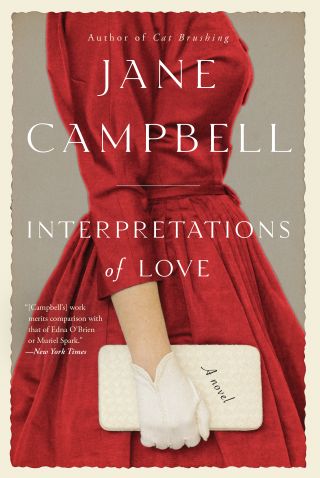

Jane Campbell, who became a debut author at 80 years of age with her book Cat Brushing, has followed up with her first work of fiction, drawing upon her 35 years of experience as a psychoanalyst. Her novel, Interpretations of Love, explores repressed emotions, memories, and unprocessed trauma.

Author Jane Campbell

Source: Jane Campbell/Used with permission

Q: In your novel, Interpretations of Love, you write, “…it is not so easy to keep the past back there where it belongs since it tends to leak into the present all the time.” Can you say more about how our past tends to leak into our present? Do you think there’s a way to stop this “leak”?

A: Remembrances from the past are all around us all the time: tunes, tastes, scents, sights, and sensations can all transport us back to the past in a manner best described by Proust in his reference to the taste of the madeleine. I doubt if it would be good to stop leaks from the past even if sometimes we wish we could. We would lose our sense of identity, which is surely composed by our histories. It is the process of acknowledging our histories and coming to terms with them that I see as the essence of the therapeutic process.

Q: Your novel explores the process of aging, and the ways we change, and don’t, as we age. You write, “I wondered whether I could try to tell her someday what it was like getting older; what the inside experience of aging is like. Not with resentment, not that. But the requirement, yes, almost the moral imperative, to grasp such gifts as life may unexpectedly offer and not to discard them as one is free to do when one is young, but to measure up to the challenge.” What has surprised you, personally, about aging? Do you think it is possible to age gracefully? If so, how?

A: In a disquisition on our vexed relationship to the past and to the future, Blaise Pascal (Pensées) points out that we focus on the past and the future and never the present. “Thus we never actually live, but hope to live, and since we are always planning how to be happy, it is inevitable that we should never be so.” The neat mathematical logic of this statement (encountered at Oxford) is one that has shaped my life. And, if not before, aging forces a focus on the present. If there have been any surprises for me, then it is simply that it is true that until one’s health fails one does not feel old, although outward appearances change so drastically. I am not sure what you have in mind by gracefully, but I suspect I would not approve of it. It sounds as though a graceful old lady would be no trouble to anyone, that she would do what she was told and obediently slide into the grave with a self-deprecating cough.

“Interpretations of Love” is Campbell’s second book and first work of fiction.

Source: Jane Campbell/Used with permission

A: I am of that group of writers who are inclined to say, “How do I know what I think until I see what I say?” This is a very subjective book; for example, my descriptions of the sands at the place I have called Merebridge (Hoylake) are both impressionistic and restricted by the limits of my memory. I could easily have done some research into the geographical features of the place and the bird and animal life etc., but I did not. These sands are the sands of my memory and to that extent are completely biographical.

It is the emotions that I attribute to Agnes that are more intriguing to me. I had not realized how important Hoylake was to me until I wrote this book. However, Agnes’s family circumstances could not be more different from my actual circumstances at the time. I have no such brother as Malcolm nor was I an orphan; it makes me wonder, however, if I felt like one. A young German interviewer suggested that when I was 4 years old and my father returned from the war where he had been held as a POW near Salzburg, I would have been told it would be a wonderful thing, and it was! BUT it meant that my small, happy, circumscribed world with my mother and great-grandmother was shattered and could never be rebuilt. He suggested that this taught me that nothing is ever perfectly good and instilled a sense in me at a very young age of the ambivalence of life…which this book goes some way to illustrate.

Q: What do you hope readers gain from spending time with Interpretations of Love?

A: Without wishing to be too grandiose, these are Proust’s words at the end of his great work: “I thought…of my book and it would be inaccurate even to say that I thought of those who would read it as ‘my’ readers. For it seemed that they would not be ‘my’ readers but readers of their own selves, my book being merely a sort of magnifying glass…it would be my book but with its help I would furnish them with the means of reading what lay inside themselves.” I cannot put it better!