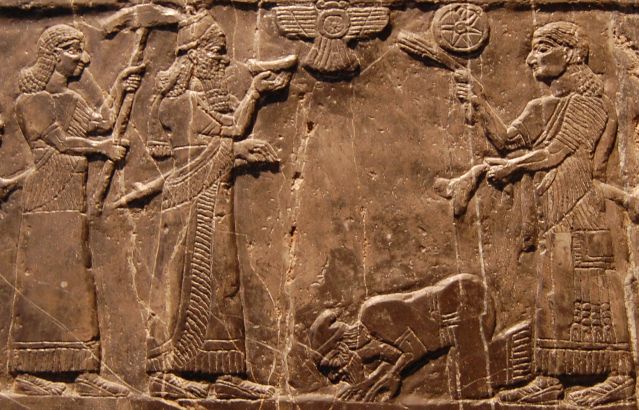

Jehu of Israel

Source: Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III/Wikipedia

It was rdj Hr-Xt, or going on your belly, in Egyptian hieroglyphics; in Greek it was προσκύνησις, or proskynesis; Latins called it adōrātiō, adoration; in Sanskrit it was प्रणाम, or praṇāma, or prostration; it was 叩头, or kòutóu, or kowtow in Chinese.

In the middle of the Middle Kingdom in Egypt, almost 4,000 years ago, a civil servant called Sinuhe came home to his pharaoh, Senusret I, and bowed down to him. “I found his majesty on the great throne in the portal of electrum. Then I was stretched out prostrate, unconscious of myself in front of him, while this god was addressing me amicably. I was like a man seized in the dusk, my soul had perished, my limbs failed, my heart was not in my body. I did not know life from death.” So pharaoh said: “Get up.” Sinuhe “places himself on his belly” and “kisses the earth.” By then, bending over was old news.

Submission can be associated with a number of emotions. Shame, envy, admiration, respect, contempt, anger and fear can be involved. Pride is generally associated with dominance, and with a “heads up” stance. Signs of submission usually include heads and bodies down.

In the Gilgamesh epic, parts of which probably go back to the 27th century BCE, an Ancient Near Eastern king struts his power like a wild bull and takes brides away from their grooms. “He will have intercourse with the destined wife, he first, the husband afterward.” But Gilgamesh is contested by Enkidu, the wild ass of a man who wins people over. “The whole land assembled about him, the populace was thronging around him, the men were clustered about him, and kissed his feet as if her were a little baby.”

Much later, in the middle of the 1st millennium BCE, Herodotus of Halicarnassus wrote about προσκύνησις or proskýnēsis, or proskynesis, in his Histories. He knew it was an old Persian habit, and he didin’t like it. “Instead of greeting by words, they kiss each other on the mouth; but if one of them is inferior to the other, they kiss one another on the cheeks, and if one is of much less noble rank than the other, he falls down before him and worships him.” Isocrates, the Athenian orator who lived a few decades later, felt pretty much the same way: “Because they are subject to one man’s power, they keep their souls in a state of abject and cringing fear, parading themselves at the door of the royal palace, prostrating (προσκυνέω) themselves, and in every way schooling themselves to humility of spirit, falling on their knees before a mortal man, addressing him as a divinity, and thinking more lightly of the gods than of men.” And after another few decades, when Alexander of Macedon conquered the Persian empire, put on a purple robe and crown and expected the subjected to bow down, his Greek friends were unhappy with him. “A distinction has been drawn by men between honors fit for mortals and honors fit for gods.”

Roman emperors, who followed a long republican precedent, absolved their subjects of proskynesis for hundreds of years. But toward the end of the 3rd century, Diocletian insisted on it. “He was the first that introduced into the Roman Empire a ceremony suited rather to royal usages than to Roman liberty, giving orders that he should be adored.”

A little more than a century later, Constantine the Great moved the capital from the Latin West to the Greek East and reestablished local customs. “He always hated brave and energetic men.” And his successors Justinian and Theodora, the empress who got picked out of the stews and put up in the palace, instructed the senate to get down. “In the case of Justinian and Theodora, all members of the senate and those as well who held the rank of patricians, whenever they entered into their presence, would prostrate themselves to the floor, flat on their faces, and holding their hands and feet stretched far out they would touch with their lips one foot of each before rising.”

Kowtowing had gone on for millennia in Asia. In the wake of Alexander’s invasion of India, Chandragupta brought the Indus and Ganges together under one yoke, and the Mauryan empire rose up. Chandragupta’s prime minister, Kautilya, wrote this in his treatise on government: “The life of a man in the service of an emperor is aptly compared to a life in fire: Fire may burn part of or the whole body, but the emperor has the power to advance or destroy his whole family.”

And kowtowing is older in China. People have been knocking their heads on the floor for the benefit of their betters since the Zhou Li, or Rites of the Zhou Dynasty, which began in the 11th century BCE. Those Rites discuss nine degrees of kowtow; the grand kowtow, reserved for an emperor, involved kneeling three times and touching the head to the ground nine times. And they had staying power. In 1793, the Hanoverian king of England, George III, received a letter from the Qing emperor, Qianlong. George, who had recently lost a war with his North American colonies, and eventually lost his mind, was reassured: “If you assert that your reverence for Our Celestial dynasty fills you with a desire to acquire our civilization, our ceremonies and code of laws differ so completely from your own that, even if your Envoy were able to acquire the rudiments of our civilization, you could not possibly transplant our manners and customs to your alien soil.” The British ambassador did as he pleased. He offered to kneel before the emperor, as he would kneel for his own king.

Other animals know how to kowtow. To vespologists, it’s “akinesis,” involving a bent head, legs, and antennae; to mammalogists, it’s “tetany,” another sort of paralysis.

Naked mole rats are small, subterranean rodents, native to the Horn of Africa and the tropical grasslands of Ethiopia, Somalia, and Kenya, who live in societies of up to hundreds of workers and a single breeding queen. She grows up to twice workers’ size and demands deference from them. They’re hissed at and shoved, after which they double up on their backs with their bodies contorted and their feet in their air. That sort of involuntary muscle spasm, or “tetany,” lasts long after the queen has disappeared.

Bugs kowtow too. Paper wasps live all over the world, on pulpy little nests made of regurgitated fibers from wood and plants. Queens use their antennae to tap dozens of helpers on their heads, abdomens, thoraxes, and eyes; and the usual response is paralysis, or “akinesis:” workers bend their heads, antennae, and legs, and are unable to move.

Other animals submit otherwise. Veiled chameleons change color; fallow deer avert their antlers; wolves lower their ears. And daffodil cichlids submit, oddly enough, “heads up.”

Daffodil cichlids, also known as the princesses of Zambia, are native to Lake Tanganyika. Pairs of dominant fish breed in underwater caves, then 1-14 subordinates help feed and defend their broods. When dominants approach, they put their heads down and subordinates raise their heads up. In crowded environments, those submission signals increase. To paraphrase the ichthyologists who study these fish, “Submission signals are less common when more shelters to flee to were available.”

Across species, subordinates react to dominants in a couple of ways. One is to get lost. The other is to go low.

Kowtow when you don’t have a choice.

Kowtow when you can’t get out.