Collecting behavior, often perceived as a benign hobby or interest, can manifest in pathological forms, particularly in individuals with specific neurological disorders.

Here, I explore the organic causes of new-onset collecting behavior, particularly in the context of frontal-temporal lobe dementia (FTD) and Parkinson’s disease (PD), shedding light on how neurobiological changes associated with these diseases can lead to altered behavior patterns. By examining the neurological pathways and the impacts of these conditions, we can gain insights into the broader implications of neurobiological functions on behavior.

Frontotemporal Dementia results in flattening of the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain

Source: Dalle-3 reworked from Alzheimer’s Association image

FTD and Collecting Behavior

FTD, a condition characterized by progressive neuronal loss predominantly in the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain, is associated with significant behavioral and personality changes. One of the hallmark symptoms of FTD is a change in social behavior, which can include developing new, sometimes obsessive interests, such as collecting (Perry et al., 2017).

The frontal lobes are crucial for executive functions, which include planning, impulse control, and judgment. When these areas are compromised, as they are in FTD, patients may exhibit out-of-character and potentially socially inappropriate behaviors. Collecting behavior in FTD patients can sometimes reach the level of hoarding, driven by reduced impulse control and poor judgment (Mitchell et al., 2019).

In-depth neuroimaging studies have revealed that atrophy in specific frontal regions correlates with the severity of such behaviors. For example, when atrophied, the orbitofrontal cortex, involved in decision-making and reward processing, can lead to altered reward-seeking behaviors, manifesting as pathological collecting (Rascovsky et al., 2011).

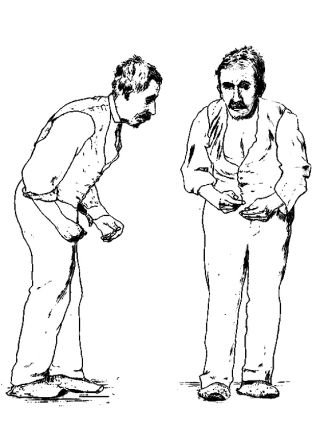

Parkinson’s patients are treated with dopamine agonists to improve movement which can cause compulsive behavior like collecting.

Source: Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Parkinson’s Disease and Collecting Behavior

Parkinson’s disease, traditionally known for its motor symptoms such as tremors and rigidity, also encompasses a spectrum of non-motor symptoms, including changes in cognitive and behavioral domains. Collecting behaviors in PD are particularly intriguing, often exacerbated by medications used to treat the disease, specifically dopamine agonists (Voon et al., 2011).

Dopamine agonists, while alleviating motor symptoms, can lead to impulse control disorders (ICDs), including compulsive shopping, gambling, and lobbyism, which includes collecting. The pathophysiology behind this involves the overstimulation of dopaminergic pathways in the brain’s reward system, particularly the mesolimbic pathway (Weintraub et al., 2010).

These behaviors can cause significant distress and impair social and occupational functioning. They are hypothesized to result from an imbalance in dopamine levels, which affects the neural circuits controlling reward and motivation. When dysregulated by pharmacotherapy, the ventral striatum, a key component of these circuits, may promote compulsive engagement in behaviors such as collecting (Callesen et al., 2014).

Conclusion

The onset of collecting behaviors in disorders such as frontal-temporal lobe dementia and Parkinson’s disease highlights the profound impact of neurobiological changes on behavior. In FTD, structural and functional changes in the frontal and temporal regions disrupt ordinary judgment and impulse control, leading to behaviors like collecting. In Parkinson’s disease, pharmacologically induced changes in the brain’s reward circuits can trigger similar outcomes. Understanding these patterns not only aids in managing these behaviors clinically but also enriches our understanding of the neurobiological bases of behavior.

This exploration into the neurobiology of collecting behaviors underscores the complex interplay between organic brain changes and behavior, providing critical insights into both the pathophysiology of neurological disorders and the broader implications for behavioral management and therapy.